Let's be honest, if you're here, you're probably staring at your nibbled flower beds at dawn or you're just plain curious about these quiet nighttime neighbors. The short answer is grass, lots of it. But that's like saying humans eat food—it's true but misses the fascinating, messy details. A wild rabbit's nighttime diet is a masterclass in survival, shaped by millions of years of evolution to avoid predators and extract every last bit of nutrition from tough, fibrous plants. Their eating habits directly impact your garden, local ecosystems, and even how you might observe them. I've spent countless quiet hours with motion-activated cameras and binoculars, and what I've learned often contradicts the cute cartoon image.

What's Inside: Your Quick Guide

Why Nighttime is Dinner Time

Rabbits are crepuscular, a fancy word for being most active at dawn and dusk. This isn't a random preference. It's a survival tactic. Their main predators—hawks, eagles, foxes, coyotes—rely heavily on sight. The low light of dusk and the cover of night provide a crucial buffer. Think of it as their version of grocery shopping in a safer neighborhood. While they will eat during the day, especially in secure, sheltered spots, the bulk of their serious foraging happens under the stars. This is when they venture further from their burrows or hiding spots to graze on open lawns, meadows, and the edges of your property.

The cooler temperatures at night also help. Digesting all that fibrous plant material generates body heat. Foraging in the cooler night air helps them avoid overheating, which is a genuine concern for an animal in a constant fur coat.

The Nocturnal Menu: From Lawn to Woodland

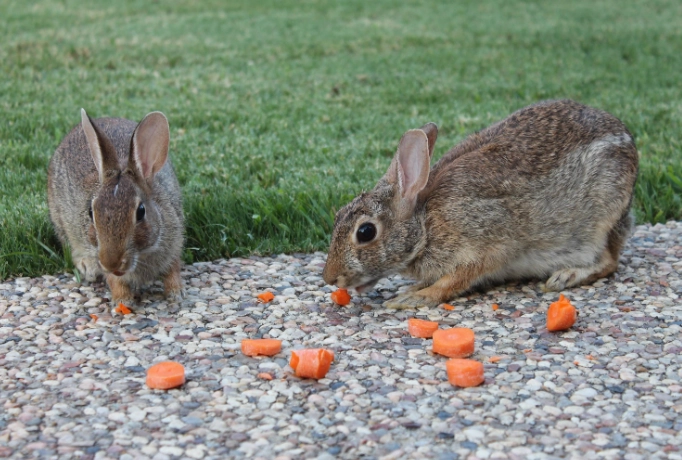

Forget the Bugs Bunny carrot stereotype. A wild rabbit's diet is almost entirely herbivorous and revolves around what's available, seasonally and locally. Their nighttime foraging is a mix of grazing (eating grass close to the ground) and browsing (nibbling on taller plants).

Grasses and Clover form the absolute staple, the bread and butter of their diet. They'll meticulously crop Kentucky bluegrass, fescue, ryegrass, and any wild grasses. White clover is a particular favorite—it's more nutritious than plain grass.

Herbaceous Plants and Weeds are the vegetables. Dandelion greens, plantain, chickweed, and wild violets are all eagerly consumed. They go for the leaves and stems, often leaving the tougher flower heads.

Garden Vegetables and Tender Shoots are the irresistible dessert. This is where your beans, peas, lettuce, spinach, and beet tops disappear to. In spring, they'll also gnaw the bark and eat the tender new shoots of young trees and shrubs, which can kill the plant—a huge point of frustration for gardeners and foresters alike.

Bark and Twigs in Winter become critical. When green vegetation is buried under snow, rabbits switch to browsing on the bark of trees like apple, maple, and willow. It's not ideal nutrition, but it keeps their digestive systems moving, which is vital for their health.

To understand how specialized this wild diet is, compare it to what a domestic rabbit should eat.

| Food Type | Wild Rabbit (Night Foraging Focus) | Domestic Rabbit (Ideal Diet) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Food | Fresh, diverse grasses & weeds (high fiber, low sugar) | Unlimited Timothy or Orchard Grass Hay (mimics wild grass) |

| Fresh Greens | Wild herbs, clover, dandelion (seasonal variety) | Limited dark leafy greens (romaine, kale, herbs) |

| Vegetables/Fruit | Rare, only if encountered (e.g., fallen fruit) | Very limited treats (high sugar is dangerous) |

| Key Difference | Diet is forced by environment; extremely high in roughage. | Diet must be carefully managed to prevent obesity & disease. |

The biggest mistake people make is assuming a pet rabbit's diet should mirror the "variety" of a wild one. It shouldn't. The wild diet is harsh and low-calorie. Pet rabbits given unlimited carrots and fruit develop serious health issues fast.

Your Garden on Their Menu: The Real Impact

So your hostas look like Swiss cheese and your bean seedlings vanished overnight. Understanding their menu is the key to protection. Rabbits have a clear hierarchy of preference.

They'll demolish young, tender plants first. Established, tough-leaved plants or those with strong scents (like many herbs) are often left alone. The damage is usually within two feet of the ground—they don't climb.

Effective protection isn't about poisons or harsh tactics. It's about smarter gardening.

Physical barriers are the gold standard. A simple chicken wire fence, buried at least 6 inches deep and standing 2 feet high, is remarkably effective. The burial prevents digging, and the height deters jumping (though some determined rabbits can jump higher).

Plant selection can steer them away. Interplant your veggies with things rabbits tend to avoid: onions, garlic, marigolds, lavender, or snapdragons. It's not foolproof, but it helps.

Habitat modification is the long-game strategy. Rabbits feel safe with cover nearby. Removing brush piles, tall weeds, and dense ground cover from the perimeter of your garden removes their safe staging areas, making them less likely to venture into the open space for a meal.

How to Safely Observe Rabbits Eating at Night

Want to see this for yourself? It's a rewarding experience. The key is to be unobtrusive. Your goal is to watch, not interact.

Location is everything. Find a spot where you've seen rabbit signs (droppings, nibbled plants) near the edge of a field, lawn, or woodland. Set up downwind, with a clear line of sight.

Use the right light. A bright white flashlight will spook them instantly. Use a red-filtered flashlight or a trail camera with night vision (no-glow or low-glow models are best). The light from a distant porch can sometimes provide just enough illumination to watch without extra gear.

Timing and patience. Be in position just before dusk. Sit perfectly still. The first rabbit might appear 30 minutes after sunset. They're cautious. One will often come out as a "scout," and if it feels safe, others will follow.

I once spent a week watching a particular feeding ground. Night one, nothing. Night two, a brief appearance. By night four, I knew their pattern: a mother and three juveniles would emerge from a blackberry thicket at 8:45 PM, graze on clover for about 25 minutes, and then move systematically along a hedgerow, sampling various weeds. This kind of specific observation tells you more than any generic article.

The Digestive Secret Behind Their Nightly Feast

Here's the part most articles gloss over, but it's the reason their diet works. Rabbits are hindgut fermenters. They eat high-fiber, low-nutrient food quickly (often at night for safety), then digest it later in a safe place.

The magic happens with cecotropes. Food first passes through and forms hard, round fecal pellets (the ones you see). But some material is diverted to the cecum, a fermentation chamber where bacteria break down the tough cellulose. This material is then expelled as soft, nutrient-rich clusters called cecotropes, which the rabbit re-ingests directly from its anus. It sounds gross, but it's a brilliant system for extracting maximum vitamins (especially B vitamins) and protein from grass.

This is why high-fiber intake is non-negotiable. If a rabbit stops eating—due to illness, pain, or a poor diet—this whole system grinds to a halt, leading to potentially fatal gastrointestinal stasis. It's also why suddenly offering a hungry wild rabbit a pile of lettuce or carrots can disrupt their delicate gut flora.

Comment